We often receive feedback from our SparkChess users and we value it greatly. Whether it’s constructive criticism, suggestions, or just a bit of praise, it’s our Northern Star pointing us in the right direction. Some bits end up as testimonials on the Download page, the rest become the source for new development ideas.

But one letter I received this week hit different. Not only an echo through time and space, but a powerful testament of how one creation, one game, can become a lifeline. I asked the sender to let us publish the email and she kindly agreed.

The email describes the precursor of SparkChess, flashChess, an app sadly no longer available online after the death of Flash. I’ve decided to publish it in its entirety, with only minor edits, such as changing the name and adding some pictures.

My name is Ann, born in 1997—the same year your website began. I grew up in a small town near X, Y Province, China. My childhood access to the internet was extremely limited. I could only use a computer with my parents’ permission, sometimes going half a year without touching one.

But I was fortunate enough to have something else: an educational device known locally as a “study machine,” something like a hybrid between an electronic dictionary and an MP4 player. Mine was from a Chinese brand called “BBK”—a company that would later evolve into the smartphone giant OPPO.

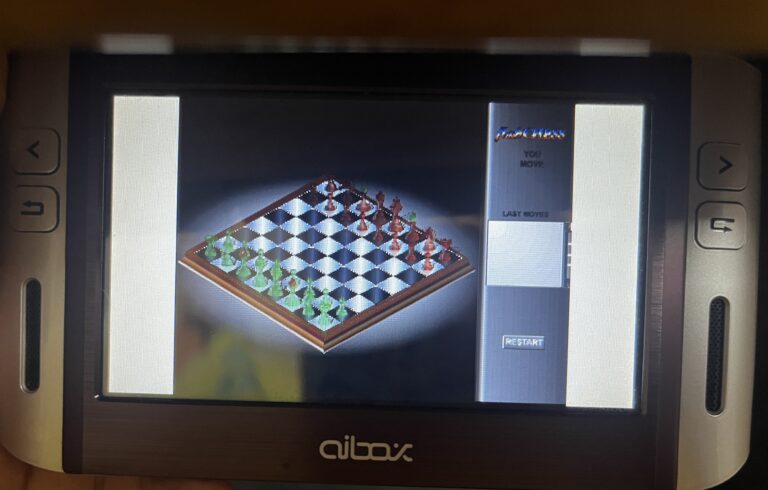

In 2011, I discovered on BBK user forums that these devices could open .swf files. That meant I could download Flash games from [pirate] Chinese sites and try to play them offline.

Most of the Flash games I downloaded never worked—either due to memory limitations or compatibility issues. But one game stood out, working smoothly and reliably: your Flash chess game. It became the only game I could always open, and in time, it became the only voice I could hear when I felt voiceless.

Even if I couldn’t use a computer for half a year, I could always open your chess game and play.

In 2011, I was in the second year of junior high school in a small town in China. That same year, I skipped a grade and took the national high school entrance exam early, earning the top score in my community and entering the best high school in Nanjing. At 14, I carried that same electronic learning device with me into this new school. The high school environment wasn’t as suffocating as junior high. But at home, the pressure remained unchanged.

My classmates began chasing after the latest iPhone 4, Nokia, or Samsung phones. But I only had a basic mobile phone that could make calls, and this one learning device.

I had never studied chess before. I didn’t know the rules—not even the concept of “castling.” It was through your game that I discovered what castling was.

There weren’t many students who played chess in school clubs, but in my spare time I tried to use the skills I had honed in your Flash game to challenge them.

Of course, I lost. I couldn’t even beat the “Deep” difficulty level of your game—how could I hope to win against kids who had trained in chess academies since childhood?

But still, I loved to play. Losing didn’t matter.

Because in a home ruled by near-tyrannical control, this game was the only pillar that held me up.

My home environment was deeply repressive. Entertainment was strictly limited. I would be beaten and humiliated just for secretly writing a diary or fiction. Every imagined sentence was subject to scorn. Even extracurricular books were inspected, and asking “why” was considered rebellion.

Since the age of eight, I rarely slept more than six hours a night. After I turned twelve, I had to wake up at 5:30 every morning and wouldn’t return home until after evening self-study ended at 11 p.m.

Yet even so, I was willing to sacrifice what little sleep I had just to secretly play the game you made, under my blanket, in the dark.

During night classes, I would hide the learning device—roughly 15cm by 9.5cm—in my pencil case and operate it with a stylus, secretly playing chess.

I also used it to read novels and listen to music. But even then, something inside me knew: this .swf file was different.

Novels, music, and comics—they were all inputs.But this chess game—it was the first time an electronic object ever gave me a reply.

It didn’t praise me.

It didn’t scold me.

It didn’t run away.

It simply answered me, one move at a time.

And that was enough.

Years later, I graduated and started working. Life has not been easy for me. The emotional environment of my family led to a long struggle with depression, and at one point, I attempted suicide.

There are over 200 scars on my arms—each one a consequence of what I endured at home.

But I gritted my teeth and chose to stay alive. And I truly believe that the Flash chess game you created played a critical role in helping me hold on.

Even though I eventually bought myself a PSP, a 3DS, spent over ten thousand US dollars on mobile games, and now own a Switch and a PS5… I still firmly believe:

If it hadn’t been for your game, I might have jumped from a rooftop on one of those nights when I couldn’t stop crying.

If it hadn’t been for your game, I might have jumped from a rooftop on one of those nights when I couldn’t stop crying.

To be honest, I haven’t played that Flash game in years. I had also stopped playing chess for a long time.

But recently, I had another painful argument with my parents. I finally voiced the suffering I had carried for so many years—I tried to reason with them, to make my pain heard.

The process was heartbreaking, but it brought some change.

After all the screaming and sobbing, I collapsed onto my bed, exhausted and broken.

And suddenly, I felt an overwhelming urge to play a game of chess.

—Like a helpless child who, no matter how old she gets, still instinctively reaches for her mother when she’s in pain.

Only in my case, it wasn’t my biological mother.

It was the Flash chessboard, the one you built—those red and green pieces arranged on a pixelated screen.

That, to me, was comfort.

I know you may no longer remember this game—but for me, it meant everything.

It became my anchor when even professional therapists didn’t know how to help me. It kept me alive.

But I want to say thank you—to you, and to chess. Your work has stayed with me for over a decade—not just as a memory, but as a model: how something modest, intentional, and thoughtfully designed can reach across time and space to make a difference.

In today’s world, we adults often worry about children spending too much time on short videos and fast-paced games.

Perhaps we can’t turn back the tide of technology, nor should we reject the power of digital evolution.

But maybe—just maybe—in the corner of an attic somewhere, there’s still room for an old chessboard, dust-covered since before the fall of the Soviet Union.

And maybe, that quiet board still has something to teach us.

Your game wasn’t a hug, or a kiss, or a line like “You’re already doing great.”

It was simply… a move: e5.

It was almost 23 years ago when I designed the flashChess interface. I still remember my initial goal: to make online chess seem easy, to let people learn as they go, and to make them feel victory is at hand. I could never have imagined that such a tiny decision maybe gave someone a reason to live. It’s humbling and overwhelming.

I don’t feel qualified to discuss topics such as parenting styles or child trauma, so I won’t. I’ll leave that to the readers.

Thank you, Ann, for inspiring me and reminding me why I create software.

I love Spark Chess, I just wish there was an option to pre-move the pieces with the mouse.

Interesting request! Could you please contact us on support@sparkchess.com and provide more details about how you’d like this feature to work?