In the United States, the word “patriotism” refers to national pride. But there isn’t a single word to refer to patriotism for one’s state. The phrase “state pride” approximates.

In Openings for Amateurs: Theory vs. Practice (Mongoose Press, 2024), Pete Tamburro’s annotations on one game included negative remarks about a Nebraskan’s chess moves. My state pride took offense!

Cornhusker Proud

I learned to play chess in Lincoln, Nebraska, and my first year and a half of rated play was as a Nebraskan. The 2024 and 2025 Nebraska Chess Hall of Fame celebrations reconnected me to the Cornhusker State. I am honored to be a member of the Nebraska Chess Hall of Fame.

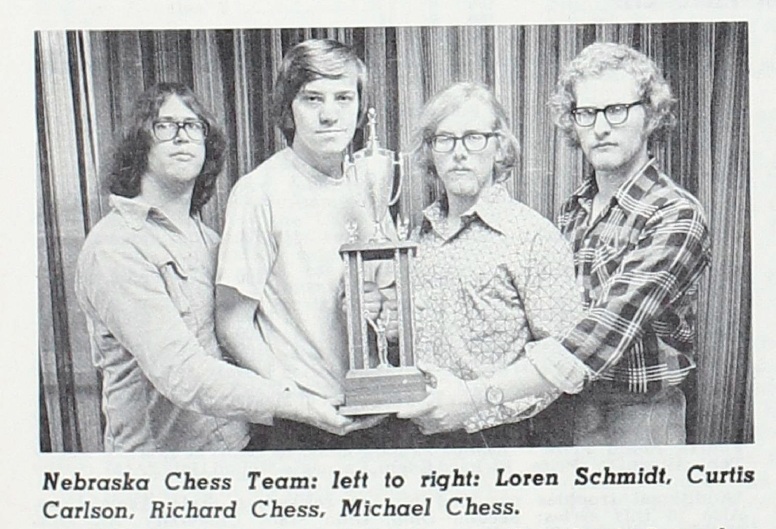

Another Hall of Fame member is National Master Rich Chess, a four-time state champion. His brother Mike Chess (1954–2019) was a two-time Nebraska High School champion. The Chess brothers were half of a University of Nebraska team that won a prestigious collegiate title.

The Pan-American Intercollegiate Team Chess Championship (Pan-Am) began in 1946 and annually determines the best college team in the Americas. Larry R. Paxton reported in Chess Life (March 1976, page 133) about the 1975 Pan-Am:

The University of Nebraska and Harvard College will share the 1976-76 [sic; should be 1975] U.S. Intercollegiate Championship title. Each scored 7½–½ at the Pan-American Intercollegiate Tournament in Columbus, Ohio. Defending champion Toronto was 7th in the record-breaking 123-team, 520-player event held December 26-30 [1975] by the Ohio State University Chess Club and the Intercollegiate Chess League of America. Finishing with 6½–1½ were The University of Chicago and Case Western Reserve University. This was the fourth consecutive Pan-Am for Nebraska’s Loren Schmidt of Lincoln, for Richard and Michael Chess of Omaha, and for Curtis Carlson of Wheatridge, Colorado.

In a Facebook post, first board Loren Schmidt, now a FIDE Master, noted that Mike Chess won the best fourth board prize with a score of 7½–½.

Martz versus Chess, North American Open 1974

Tamburro introduced the Martz versus Chess game: “Andy Ansel, chess book collector extraordinaire and superb chess researcher, also collects notebooks left by masters. His column in American Chess Magazine is called, ‘Unknown American Chess Games.’ He writes an appreciation and history of a noted American master, and I [Tamburro] annotate most of the games he finds. This game by IM Bill Martz is a brilliant selection.”

Since Tamburro’s book listed Black only as “Chess,” I wondered if Martz was playing against Rich Chess or Mike Chess. I emailed Pete Tamburro and Andy Ansel to find out. Ansel replied with a PGN of the game, which he got from an unpublished notebook belonging to Bill Martz. Mike Chess was Martz’s opponent.

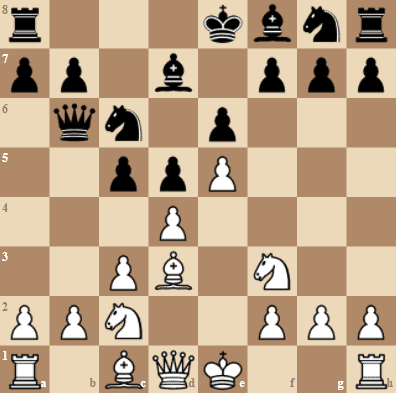

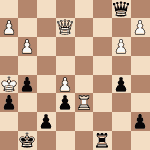

Here is the game, without most of Tamburro’s annotations and diagrams. But I am including his excellent choice of a first diagram and his pertinent question about White’s plan after 11…a6.

Pawn Chains

Tamburro’s first diagram after 11…a6 shows a crucial moment in the game. In answer to his question about White’s plan, I thought that White should play for c5 because White’s pawn chain is pointing toward the queenside and the center is blocked. The “pointing” idea is explained in many places, such as this diagram and excerpt from an article on Chessable:

Notice how the center of the board is locked together with pawns, creating a sort of “no man’s land” in that area. That indicates that each player should attack on the wings. A good rule of thumb in these types of positions is to attack in the direction of your pawn structure. Therefore, Black should attack on the queenside while White should attack on the kingside.

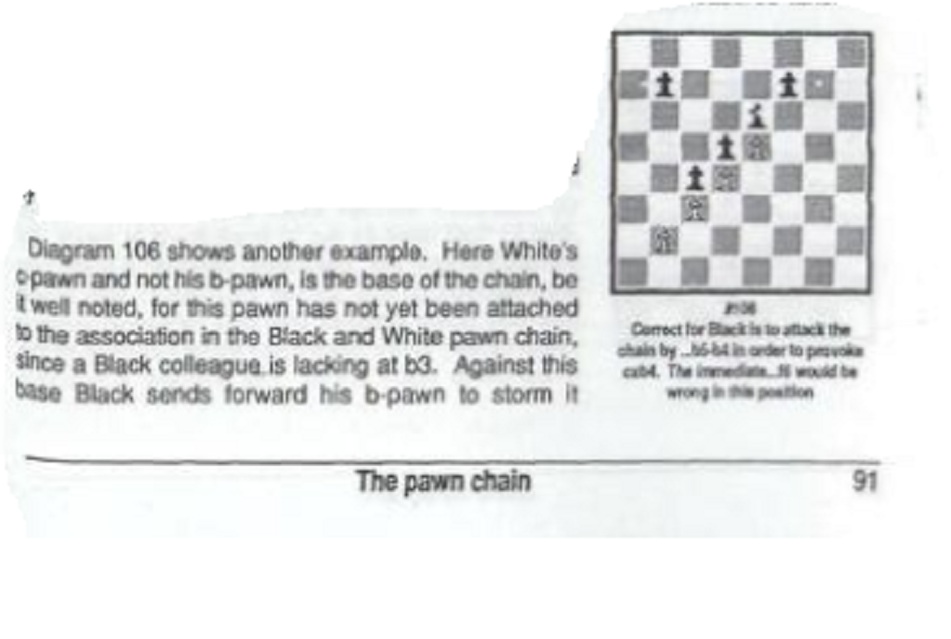

Another way to figure out White’s plan is to think about how to attack the base of Black’s pawn chain. According to My System by Aron Nimzowitsch, a pawn can be a chain’s base only if it is opposed by an enemy pawn. That is, blocked.

Nimzowitsch gave this diagram on page 91 of his classic, explaining that White’s pawn chain begins on c3 because the c3-pawn is blocked by Black’s pawn on c4. Although it might seem that the b2-pawn is the base of White’s chain, it is not. White’s b2-pawn is not blocked by a black pawn (which would have to be on b3). As it is, White’s b2-pawn is not a base. Therefore, Black should aim to play …b5 and then …b4 to attack that base c3-pawn.

By analogy, in the Martz–Chess game, White should attack Black’s d6-pawn as it, not the c7-pawn, is the base of Black’s pawn chain. Attack where your pawn chain points and attack the base of your opponent’s pawn chain are two important ideas, but Tamburro did not mention them in his annotations to this game. Instead, he asked readers to look for weak squares and to replay the game multiple times to learn from it.

Notation and Annotations

Before I discuss annotations further, a note about notation. Tamburro’s book uses figurine algebraic notation. That is, instead of “B” to express the move 2…Bg7, as I have written below, there is an image of a bishop before “g7.” Figurine algebraic notation looks great in Tamburro’s book, but I don’t know how to reproduce it here.

Regarding the Martz–Chess game, Tamburro failing to mention pawn chains was an error of omission. He made errors of commission too, as shown in this quote from page 130:

1.c4 g6 2.e4 Bg7 In the June 1972 issue of British Chess Magazine, William Harston wrote an article, “The Anti-anti-Grünfeld.” He spent more than three pages on it, but apparently Mr. Chess [yes, that’s his name – ed.] didn’t read the literature, or perhaps was suspicious of it: 2…e5.

These first two moves are not a Grünfeld nor are they an anti-Grünfeld or an Anti-anti Grünfeld. A Grünfeld requires a knight on f6, and Black hasn’t played …Nf6. Typically, a Grünfeld begins 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 d5. An anti-Grünfeld usually begins 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.f3.Even an Anti-anti Grünfeld requires that Black play …Nf6.

Inaccurately naming an opening is a problem in a book whose title contains the word “Openings.” Another problem is Tamburro implying that Mike hadn’t read chess literature. A third problem, or at least something that I found distracting, is for an editor, whose chess credentials were not formally introduced, to insert remarks in this annotation and elsewhere. I checked with Tamburro and the editor responsible for bracketed remarks is listed on the copyright page, Jorge Amador. Tamburro’s page 130 continues:

3.d4 d6 4.Nc3 Nd7 Does anyone still play this junk?

This question is the first line of his annotation after 4…Nd7, though he also acknowledged that there are 4,000 games with this move for Black.

When presenting the entire game earlier in this article, I included his annotation, after Black’s move 11, “Does anyone else want this?”

In my opinion, the tone of Tamburro’s annotations and rhetorical questions insults the chess legacy of Mike Chess. Tamburro calling Chess’s moves “junk” and asking, “Does anyone else want this?” are two examples of why I was offended on behalf of Chess and Nebraska.

Promotional Video and Ordering Information

The Martz–Chess game is featured, from minute 26 to just after minute 29, in the Forward Chess channel’s video promoting Openings for Amateurs: Theory vs. Practice. Of the 38 games [Edit: 85 games is correct] Tamburro annotated for this book, this game is clearly one of his favorites.

The copyright date in the printed book and in the Forward Chess app is 2024. But this Mongoose Press webpage lists “February 2025 Paperback.” The paperback is $24.95.

It’s easier to read the Forward Chess version of Tamburro’s book, as then one can click through the moves and use the built-in Stockfish 16 engine. The Forward Chess version is $17.99 and is available at this link.

Chess Journalists of America

Openings for Amateurs: Theory vs. Practice won the 2025 Chess Journalists of America “Best Instructional Book of the Year Award.” For a list of all the 2025 award winners, go to this link.

I read, with some amusement, WIM Alexi Root’s “book review.” Maybe it should be called a “game review” as she decides to go off on a spirited defense of Mike Chess, the loser of a brilliant overall conception by Bill Martz. She went, as did Penny in The Big Bang Theory, “all Nebraska” on me. How dare I call Mr. Chess’s 4…Nd7 junk?? Let’s have some fun and read my usage of that word in context: ““Does anyone still play this junk? Oh, yeah! Over 4,000 games with this for Black and some famous GMs to boot. It creates complications and often puts opponents on their own without their precious little book lines.” A fair reading would conclude that at the very least associates our allegedly insulted player of the Black pieces with a whole bunch of adventurous types and some GMs.

Who was really insulted was IM Bill Hartston, whom Root lectures on the definition of what a Gruenfeld Defense is, which is pretty funny because in 1971 Hartston came out with what then was THE book on the Gruenfeld. I cited the IM’s June 1972 article in BCM where he explains why he titled it the Anti-anti-Gruenfeld. Although he uses several interesting paragraphs to explain, basically it’s an attempt by Black to avoid the Anti-Gruenfeld when he realizes that White is trying to avoid his Gruenfeld (he uses Botvinnik as an example of this—who also wrote a book on the Gruenfeld) to cross White’s intention to go into a normal King’s Indian—thus, humorously, Hartston defends his title with “And why not? They have anti-missile missiles, don’t they?” It’s an opening transition dance, and his full article is a wonderful lesson.

The transition that made me utterly fascinated is WIM Root’s turning a lesson on the King’s Indian and how to exploit weak squares into a lesson on the Advanced French, which is quite an achievement. She does a fine job with explaining attacking the base of a pawn chain. Of course, when I wrote this for American Chess Magazine, I had limited space [as I did with the book at 300 pp.], so I concentrated on the brilliant—indeed unique—Martz plan, the point of the lesson: castles queenside, then moves both his king and rook over one to pave the way for control of the c-file and backwards develop his two knights to the first rank, followed by TWICE doing the same maneuver to exploit Black’s weak square weaknesses. It is, admittedly, one of my very favorite games in the book of 85 annotated games, not 38, btw. I hope Forward Chess didn’t shortchange her! If the editor of this site so wishes, I would be happy to reproduce it to allow readers to decide for themselves.

I do commend Alexis for reproducing the Book of the Year (instructional) award I received. My greatest reward is that I have been invited this weekend to a celebration of a former student of mine becoming a master, who wrote to invite me and said my books were the only ones he ever read. Although the average or club player is my target, I do get nice messages from titled players as well. One requires my first OFA to be purchased by his students, so if you’re a chess teacher there’s a trilogy of lesson games. 200+ games and 900+ pages. Lots to study! And some fun chess history stories from my 60+ years of playing chess and meeting chess players.

William Martz was an IM and Mike Chess was a strong 2100 player. Losing a hard fought game to an International Master should not subject a 2100 player to insult regardless of what state he is from. Your bias is showing and is somewhat embarrassing to defend.