In chess it’s important to make sure you’re comfortable with the positions that arise from the choices you make early in the game.

One position may even be objectively better. But as long as they’re both playable, if the first position doesn’t fit your style, the other one is your best choice.

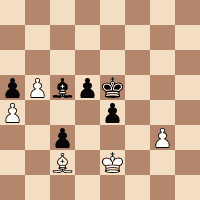

The game below serves as the base of the article. Play through it and refer to it when you want:

We all play some positions better than others

Only someone with inside information could possibly understand why I have adopted 1...d6 as my defense against the queen pawn.

It happened a couple years ago, and here’s why.

I play the Leningrad Dutch well, because it leads to unbalanced positions with a high degree of complexity. That fits my style, and my performance rating with the Leningrad is well over 2200.

However … I intensely dislike playing against the Staunton Gambit (1. d4 f5 2.e4).

Black is considered perfectly fine in this chess opening. However, he enters the middle game with holes in his position, awkward development, and White has all the dynamic chances.

That’s not how I like to play!

When you think about it, the whole reason we play chess online is because we enjoy it. And the bottom line is that it takes all the fun out of life, when we end up playing positions we don’t like. Of course that happens to all of us from time to time, but we don’t want it to be programmed directly into the opening.

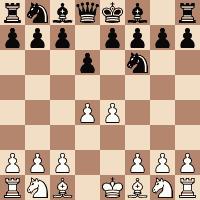

After 1...d6, 2.c4 is the move that comes most natural to a player who opens with the queen pawn. Then I play 2...f5, and now the Staunton Gambit is no longer sound. That’s because 2.c4 is a strategic move designed to gain space on the queenside. It’s not in the spirit of a dynamic opening where every move counts.

The other thing I like about 1...d6 is that it’s not played often. That means there’s a good chance my opponent won’t know the intricacies of the variations.

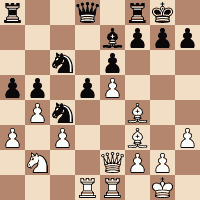

3. Nc3 c6 4. Nf3 Bg4 5. Be2 e6

The idea of this opening is to change the pawn structure with d5, so we end up in a position where Black plays a French Defense without a bad bishop.

It’s true that Black takes two moves to play d5, but this loss of time is not so important in a closed position. Chess is a game of tradeoffs. In this case we’re sacrificing a little time in order to eliminate our piece with the least potential.

6. O-O d5 7. e5 Nfd7 8. Bf4 (e3 is a better square) Be7 9. h3 Bh5 10. Qd2 c5 11. dxc5 Bxf3

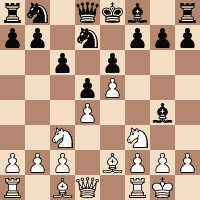

A key point in the game. If I recapture on c5, White gets a classic post on d4 for his knight. Given the pawn structure on the board, and all other considerations, my assessment was that in this position White’s knight on d4 played a more important role than his bishop on f3.

In reality, the two positions (with or without the capture on f3) are almost exactly equal. That means we return once more to our theme. When you’re uncertain, play the position you like the best.

I don’t like giving my opponents easy moves and classical play. Even though the two positions are objectively equal, White will have to work hard to find the best squares for his bishop. On the other hand, his knight would immediately be well posted on d4.

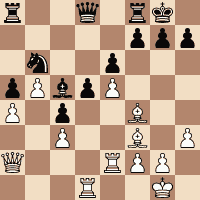

12. Bxf3 Nxc5 13. Rfe1 Nc6 14. a3 a6 15. b4 Nd7 16. Na4 b5 17. Nb2 Nb6 18. Rad1 O-O 19. c3 a5

Seeking to open lines on the queenside where Black’s play resides. However, “every move creates a weakness.” I didn’t think about the pawn on b5 when I played this move, and now I was facing an unexpected problem to solve.

20. Qe2

I was irritated that I didn’t consider this move. Not only that, the computer says 20.Be2 was even better. This kind of simple omission is a mystery, especially since I frequently calculate combinations 7-8 moves deep.

One grandmaster calls this phenomenon a “blind spot.” In my opinion it’s caused because you don’t ask yourself a few key questions before you make your move. If I’m analyzing a critical variation, I inspect it very carefully. Not every move receives the same degree of attention.

20... Nc4

Renew your warrior spirit after every oversight

20...ab was better for reasons that will soon become clear.

Oversights and inaccuracies can snowball on the chessboard. After making the initial oversight I lost my clarity and focus, because my irritation was clouding the analysis.

I have learned that it’s often a good idea to get up from the board for a couple minutes after making an oversight. Just walk around, take a few deep breaths, and dedicate a few moments to clearing your mind.

That negative emotion can affect your analysis adversely, and you won’t even realize it’s happening until you’ve made a second mistake. Fortunately, in this particular contest, these oversights weren’t lethal, but they did cause drastic changes in the position.

Have a strategy for how you respond to oversights

- First of all, you have to expect them.

- Personally, I’ve made inaccuracies in at least 99% my victories. Maybe I played a perfect game once … I just can’t remember if I did … and the odds are against it.

- View each error as a test of character. Respond to your mistakes with increased mental fortitude, and an absolute commitment to make the most of your new situation.

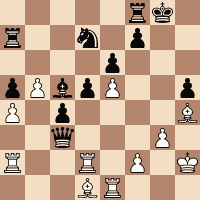

21. Nxc4 bxc4 22. b5 Nb8 23. a4 Nd7 24. Qa2

Seek to centralize your pieces

24. Qc2 was better. Why position the queen way out on the side of the board?

Let’s pretend you’re looking at two different squares for a piece, and you’re not sure which one is best. Pick the most central square, because it will have the most influence in the greatest number of variations. It won’t always be the best square, but it has the highest probability of being the best move.

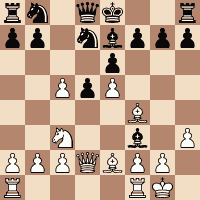

Bc5 25. Re2 Nb6 26. Bg3

Sometimes someone plays a certain move, and I “just know I’m going to win.” I’ll admit this is an irrational instinct, because I’m still “not winning yet.” However, I’ve found it comes true the vast majority of the time.

My opponent’s last move was so bad that it told me he didn’t understand the position. My bishop on c5 is a great piece, and should be challenged immediately. Instead, he put the piece that was needed to oppose it on a square that was basically dead.

26... Ra7

The idea is to get away from his Bishop on f3 and play d4 in a lot of variations. The sequence would be a queen move, followed by ... Rd8 ... Rd7 ... and finally d4. This is an active plan which looked appealing when I played ...Ra7. Of course, only the exact position on the board would determine whether it would be correct when it came time to proceed.

27. Red2 Qg5 28. Kh2 h5 29. h4 Qf5 30. Re1

This move puts the question to my queen. I knew there was a shortage of squares on f5. I looked around before I made the commitment, and didn’t see a way that White could refute my idea.

However, only about a minute after making the move, I suddenly noticed that Re1 cleared d1 for the light squared bishop on a journey to c2, and I became very concerned.

30...g5

The only good move. It was essential to get some squares for the queen.

31. Bd1 gxh4 32. Bxh4 Nd7 33. Bc2 Qg4

But not 33... Qf4+ 34. Bg3 Qxd2 35. Bh7+ winning the queen

34. g3 Qf3

And now I felt good again. White ended up weakening his light squares as a result of my queen maneuver, and I’m now attacking c3 and f2.

35. Bd1

Without going into the details, 35.Qa1 was the only move to hold the balance. This would be an extremely difficult move for anyone under 2400 to find, because it doesn’t suggest itself to the intuition, meaning it would only become apparent after deep analysis.

White reasoned that he would trade pawns. Unfortunately, in this position his c pawn is much more valuable than my h pawn, and that’s worth a little commentary.

I have weak squares all over my kingside, and if White could maneuver one of his rooks or his queen to that side of the board, or if he had a knight sitting on a square like f6, the game would probably end very quickly.

That’s why we can’t rely upon “general principles” alone. Every position is unique.

35... Qxc3 36. Bxh5 Nxe5

The computer likes 36... Bxf2 better by a large margin. However, I don’t care about that. We’re nearing move 40, and I was short on time. The move 36...Nxe5 was simple and clear. I looked at 36... Bxf2 briefly, and immediately became confused.

Speaking practically, and back to the theme we’ve already touched upon, sometimes the best move isn’t the one that “gives us the largest advantage.”

Sometimes, the best move is the one we understand clearly, and can play quickly without spending a great deal of time and energy. I like what I recently heard a superstar employee say in the workplace, “I’m not paid to be perfect. I’m paid to be productive.”

37. Bf6 Nf3+ 38. Bxf3 Qxf6 39. Kg2 Kg7

A dramatic moment – two moves left and about a minute on the clock. I saw ...39 Bb4. With time to analyze properly, I would have played the move. However, it incurs some risk. White’s b pawn would no longer be blockaded, and I was also looking at a mate threat on h7 after Qc2.

In reality, both threats are easily defended, but I’ve learned an important lesson over the years. I frequently encounter scenarios where I know I’m winning, have two choices, and one involves some risk.

The long hard road of experience has taught me to avoid the risk, even if the other move is more aesthetic, or probably leads to a quicker win.

Sometimes questions are the answer. We’ve all heard about the pitfalls that can arise in the process of “winning a won game.” Here’s a good question to ask yourself, and this one is definitely worth some rating points,

“What’s the only way I can lose this game?”

In a future article, we’ll revisit this topic and generate a list of well-framed questions to help guide your decisions. As time goes by, you’ll definitely get increasingly better at “managing your mind at the board.”

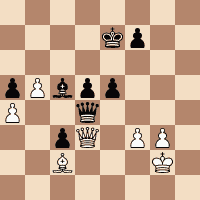

40. Rh1 Rh8 41. Rxh8 Kxh8 42. Rd1 Kg7 43. Rh1 Ra8 44. Qc2 Rh8 45. Rxh8 Kxh8 46. Qd2 c3 47.Qc2 Qd4

This move illustrates a best practice for those times when you have a large advantage, and your opponent has no constructive way to improve his position.

It often pays to take your time and optimize all your pieces before trying to convert your advantage into a win. As you become optimized, you will often find that beautiful variations begin appearing on the board. And even if the win ends up as simple and mundane, that’s okay too. In the end, scoring the point is what really counts.

48. Bd1 Kg7 49. Qe2 e5 50. Bc2 Kf8

Played to get away from the possibility of any checking sequences, by sheltering my king behind the central pawn wall. Specifically, I was looking at playing e4, and wanted to deny White the opportunity of Qg4 check.

51. f3 Ke7

At this point I saw a clear winning plan.

Right now White’s king will escape to g4 if I play Qg1 check. However, I can prepare the check by bringing my king to e6 and then playing f5. The pawn on f5 will control the escape square on g4.

After that, when I check on h1, White will have to put his queen on h2, and then I capture on f3. White will be compelled to resign soon afterwards.

52. Qd3

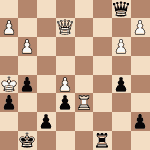

There’s a nice combination here. See if you can find it.

52... Qxd3 53. Bxd3 f5 54. Kf1 e4

If I didn’t see this sequence, I would have analyzed Qf1+ on move 52. The game continuation was simple and clear, so there was no need to spend time and energy on that analysis.

53... f5 was vital.

If I tried to prepare the pawn advance with 53...Ke6, than the game would be drawn after 54. g4. After that, White can trade his e pawn for my f pawn, and then blockade my passed pawns on the light squares.

Be careful with opposite color bishops

Sometimes even a two pawn advantage isn’t enough to win. As always, it depends upon the position. I knew without question that three connected passed pawns would score the full point.

When you look at the actual position on the board, it’s almost the same as having a three pawn advantage, because all of White’s pawns are useless.

55. fxe4 fxe4 56. Bc2 Ke6 57. Ke2 Ke5 resigns.

A very interesting game!