Having achieved notable chess-playing results, many prominent chess players switch from chess playing to advocating for chess. One example is Grandmaster Nigel Short. At his peak, Short was ranked #3 in the world. Now Short is a FIDE (International Chess Federation) Vice President. In this article, after brief remarks about FIDE officials, I share my own journey from chess player to chess advocate. I also discuss “Girls/Women in Chess” and “Chess in Education.”

Grandmaster Nigel Short, on Twitter, notes that he is a FIDE Vice President and “the only player ever to win chess tournaments in six continents.” Short travels constantly, promoting chess everywhere he goes. When he was in Dallas in September of 2019, I posted for a photo with him. To make a “Short” joke, there is no “shortage” of top chess players serving FIDE.

Another renowned chess player, turned chess advocate, is FIDE Director General Emil Sutovsky, a grandmaster. Sutovsky was the 1996 World Junior Chess Champion and is a mainstay of the Israeli Olympiad chess team. Other FIDE officials, who are chess-playing luminaries, include FIDE Vice President Julio Ernesto Granda Zúñiga, a grandmaster and four-time champion of the Americas; and former Women’s World Champion Zhu Chen, who is FIDE’s Treasurer. Grandmaster Judit Polgár, who was once ranked #8 overall in the world and is the greatest female chess player of all time, is an Honorary FIDE Vice President.

My own journey is less prestigious than those of the FIDE officials already mentioned, both in terms of chess-playing and chess-advocacy accomplishments. My most famous chess-playing accomplishment was winning the U.S. Women’s Championship in 1989. Because of that victory, I became a Woman International Master. For the 1990 U.S. Women’s Championship, US Chess (then known as USCF) proposed to cut that championship’s field from 10-12 players to the three highest-rated players and the defending champion. Although that would have personally benefitted me as defending champion, as the prize fund would be shared among four players rather than 10, 11, or 12 players, I opposed the measure. You can read about my opposition in an editorial on page 2 of the April/May 1990 California Chess Journal.

To oppose the switch to four players for the 1990 U.S. Women’s Championship, I started a successful petition drive, mailing over 800 signatures to USCF. In 1990, the U.S. Women’s Championship had 10 players. The tradition of inviting 10-12 players to the annual U.S. Women’s Championship continues to the present day.

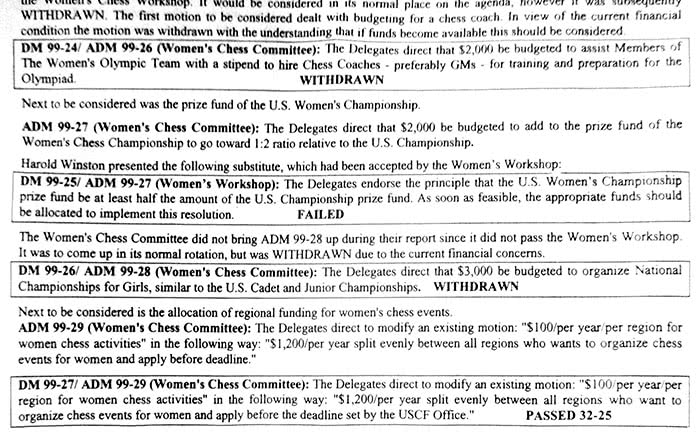

Subsequently, I spent even more time advocating for women in chess, chairing the USCF Women’s Chess Committee, organizing chess events, and leading chess in education initiatives. Regarding women in chess, another motion was for the prize fund for the U.S. Women’s Championship to reach the level of ½ of the overall U.S. Championship’s prize fund. That motion failed in 1999, but it has come true today. In 2019, for example, the prize fund for the U.S. Women’s Championship was $100,000 and for the U.S. Championship $194,000.

In 1998, I organized a USCF Region 10 Women’s Championship. I rented the Civic Center in downtown Denton, TX for the event. There were 11 participants in that Region 10 Women’s Championship. However, I organized other events that same day, such as my giving a simultaneous chess exhibition open to all, that brought the total attending higher. In 1999, I was successful in having the USCF allocate $1200 per year, to be split among regions (there were 12 regions in USCF) that wanted to hold women’s chess events. Regional Women’s Championships are still happening as of 2019. There is also now an active and funded US Chess Women in Chess Initiative.

I make a point of never separating girls and boys, nor awarding special prizes for girls […] because in the end, our goal must be that women and men compete with one another on an equal footing

GM Judit Polgár

On November 30, 2019, Grandmaster Judit Polgár wrote, “I make a point of never separating girls and boys, nor awarding special prizes for girls . . . . Meanwhile, national federations use their resources, and public subsidies are creating more female-only competitions. It is high time to consider the consequences of this segregation – because in the end, our goal must be that women and men compete with one another on an equal footing.” Here is her editorial. The London Chess Conference, profiled in an earlier SparkChess article and with Judit Polgár as Honorary Director, will also be a rich source of ideas about “Chess and Female Empowerment,” as the conference’s website and Twitter feed will post summaries and reports in the days and weeks to come.

Theories and research about female academic achievements in all-girls schools and women’s universities, stereotype threat, and gender stereotyping could inform discussions about the value of separate chess events for girls and women. That is, there may or may not be value in separate chess events for girls and women; both informed theories and further research are needed. In any case, it is clear that the topics of “girls/women and chess” and “chess in education” are intertwined.

Not surprisingly, considering that the topics are intertwined, I also served as co-chair of the USCF Chess in Education committee. That committee has since been disbanded by US Chess (as of 2019). Through the years that I was co-chair or a member of it, I co-organized chess in education conferences and workshops, at U.S. Opens (see this link for one example; see this link for another example), at Texas Chess Association tournaments (for one example, see this link), and at UT Dallas, in 2001 and 2011. For 2011, view the papers presented at this link. Currently, FIDE (International Chess Federation) has a Chess in Education Commission. And on November 24, a new Chess: Education and Science journal was announced.

I also have volunteered in public schools and in libraries to promote chess. I told about some of those efforts in this US Chess “One Move at a Time” podcast episode. I am also constantly writing about chess, both here on SparkChess and elsewhere. I write my articles to promote chess and its connection with other parts of life. Of course, I am also interested in writing more articles about the topics of “Girls/Women in Chess” and about “Chess in Education.”

However, as mentioned in that linked podcast episode, I have another topic I’m working on. Please let me know about people (or about yourself) who are involved in chess and dance for an upcoming article in Chess Life. Leave a comment here on SparkChess, or contact me via my email address at The University of Texas at Dallas “aroot at utdallas dot edu” or via Facebook.