Certain emotions may distract chess players from finding good moves. This article suggests two strategies, let it go and avoid obsessions, that may help players achieve emotional states which are better for chess.

Candidate Moves

Defending Under Pressure: Managing Your Emotions at the Chessboard by Dr. Steve Hrop advised taking deep breaths and finding candidate moves. Useful advice, which I will implement in future tournaments. However, I had not yet read Hrop’s book when I played an afternoon rapid tournament on February 19, 2022.

Instead, I implemented two other strategies—“Let it Go” and “Avoid Obsessions”—that helped me replace my agitated emotional state with one better suited for playing good chess moves.

Let it Go

I don’t like when my opponents adjust the chessmen on my time. Legally, they are supposed to keep their hands off the board while my clock is running. Yet calling the tournament director over seems like a big hassle. Often, I’ve asked opponents to stop adjusting on my time, which means I’ve committed the infraction of talking to my opponents. Chastising them usually makes me feel upset, and not in the right mood to find good chess moves.

On February 19, chess master Marcin Chmiel adjusted one of his chessmen on my time. I found a novel way to let my annoyance go. I thought about how Chmiel had not complained that I had rotated the board, before our game began, so that I sat facing the tournament room with my back to the wall. Chmiel’s back almost bumped up against the back of a player in the next row. Since Chmiel pleasantly let me have the best seat, I decided to ignore his adjusting infraction. Thinking of how he gave me the best seat, I felt kindly toward him. That peaceful emotional state helped me focus on a good next move.

Avoid Obsessions

In my previous tournament at the Texas Chess Center, on January 22, I scored 1.5 out of 4 against players with lower ratings than mine. During that tournament, I filled out the header of each scoresheet with my opponent’s name and rating. Each scoresheet reminded me that I might lose to a lower-rated opponent. That is, my hand-written ratings heightened my already excessive focus on ratings.

The tournament had a fast time control: game in 30 minutes with 5-second delay (per move). That’s known as “G/30 d5.” Each game takes at most about an hour (around 30 minutes for each side). The delay means your clock ticks off five seconds before it starts counting down, per move. After either you or your opponent have less than five minutes, each of you may stop taking notation. If you lose on time, you lose the game unless your opponent does not have mating material. For example, if my time ran out but my opponent only had a king and a knight (not enough to implement a checkmate) our game would be a draw.

On January 22, even though I could have stopped notating when my opponent’s clock or my clock went under five minutes, I kept notating each game. Likely, the seconds I spent notating meant fewer seconds to find the best moves. Yet, I was obsessed with having a record of each game to review later. Maybe I was like people who forego enjoying the scenery to take photos, obsessed with their upcoming posts on Instagram.

On February 19, I left the top of each scoresheet blank: No names, no ratings. Names and ratings can be filled in afterwards, at the site if you are required to turn in your scoresheet or later, at home, using the tournament’s online rating report.

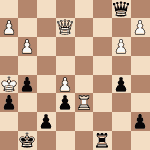

My third-round opponent (Marcin Chmiel) in my February 19th tournament turned down my two draw offers. I made my first offer on move 13, when Chmiel had about 10 minutes left, and I had around 12 minutes left. I really didn’t want to get into a time scramble. When he refused, I thought to myself, “Well, I just have to make the best of it and keep trying to make good moves.” When Chmiel’s clock went under five minutes, I stopped taking notation. I made a second draw offer when I had 6 minutes and 35 seconds left and he had 1 minute and 35 seconds left. Soon after he refused that offer, he blundered. I won, on the board rather than on time. Chmiel said after the game that he had pressed too hard for the win.

More than a week later, I showed the first part of the Root–Chmiel game at the Mechanics’ Institute Chess Café. More than half the game was not notated, and, sadly, I could not remember it.

On February 19, I won first place. My 4–0 score earned the $200 top prize. Jarred Tetzlaff, Managing Director of the Texas Chess Center, presented me with my check while Texas Chess Center coach Ryan Deering snapped a photo. Thanks to the Texas Chess Center for its generous policy of free entries to titled players; I’ll be back!